From the Courts to the Commission: How U.S. Youth are Globalizing the Fight for Climate Justice

By: Stephen Badea

In August of 2015, 21 plaintiffs from all over the United States, all under the age of 18, sued the United States in Oregon federal court. Juliana v. United States alleged that the plaintiffs' constitutional rights to life, liberty, dignity, personal security, and more were being jeopardized by the U.S. government due to its omission to do anything regarding climate change despite full knowledge of its detrimental effects.

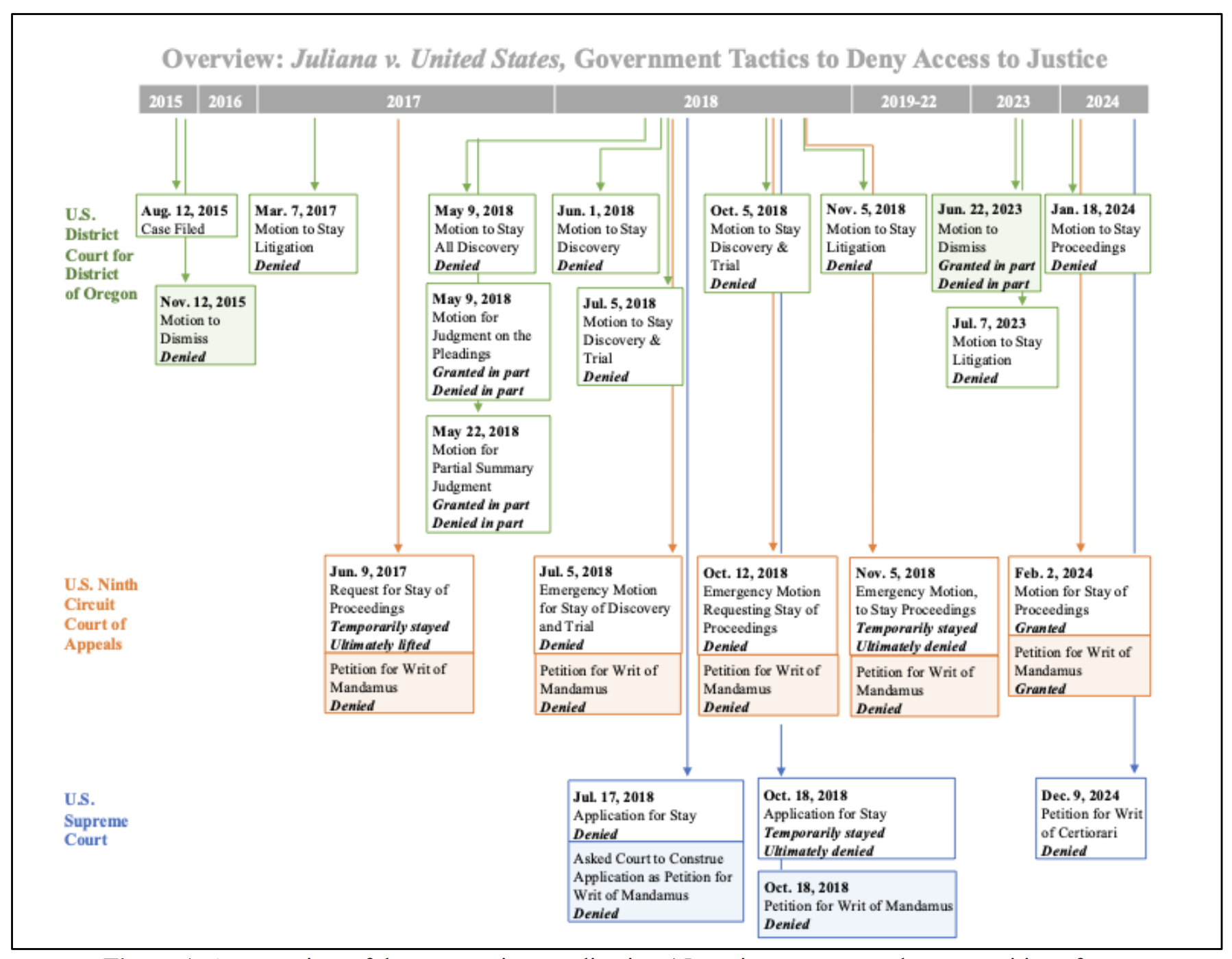

The 21 youths in Juliana litigated tirelessly through all levels of the federal court system for ten years, to no avail. Over that period, they faced relentless opposition and procedural obstruction from the government. The U.S. Department of Justice filed two motions to dismiss, fifteen motions to stay the proceedings, and seven petitions for a writ of mandamus before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court.

While the Ninth Circuit found that the plaintiffs had proven damages and that those damages correlated with the actions of the U.S. government, the court ultimately decided to remand the case to the District Court on redressability grounds, with instructions to dismiss. In essence, the court stated that the relief the plaintiffs sought was beyond the court’s power, contrary to the opinions of numerous courts worldwide, as well as to several recent influential advisory opinions. Unfortunately, the journey of Juliana through the federal courts ended on March 24, 2025, when the U.S. Supreme Court denied the plaintiffs’ petition for writ of certiorari.

But did the Juliana plaintiffs stop there? Absolutely not.

On September 23, 2025, 15 of the original 21 plaintiffs, represented by Our Children’s Trust, filed a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (“IACHR”), Organization of American States (“OAS”), alleging that the U.S. government’s actions not only threatened their lives but also constituted violations of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man.

Specifically, the petitioners ask the IACHR to find the United States in violation of Articles I (life), II (equality), V (private and family life), VI (family), VII (special protections for children), IX (inviolability of the home), XI (health), XIII (cultural life), XVIII (access to justice and effective remedies), XXIII (property), and XXIV (prompt and effective remedy) of the American Declaration, and the rights to dignity (Preamble).

While the petition is yet to be decided by the IACHR, it represents a powerful step in the right direction toward ultimately obtaining relief for the Juliana petitioners. By petitioning the IACHR, they are opening the door for international representatives to potentially conduct an on-site visit to the United States and meet with the petitioners themselves to get a firsthand understanding of how United States’ policies not only harm citizens but also undermine human rights as a whole.

Additionally, should the petition be granted, this move by the petitioners would allow the IACHR to conduct hearings as necessary to facilitate further fact-finding. All of this would advance the goal that the Juliana plaintiffs could not achieve in federal court: having a tribunal use its power of judicial review to hold the other branches and agencies of the U.S. government accountable for their willful neglect in addressing the climate crisis.

Even if this were to happen, how would the United States comply?

The IACHR’s recommendations cannot, by themselves, compel the U.S. to act. Despite being a member of the OAS, the U.S. has neither ratified the American Convention on Human Rights nor accepted the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ (IACtHR) contentious jurisdiction, preventing cases from being brought to or against the U.S. before the IACtHR. Therefore, referral of a petition to the IACtHR would not result in a binding decision against the U.S. Nevertheless, such recommendations could still prompt change through other means. A report from the IACHR explicitly outlining the United States’ human rights violations and repeated failures to act in the best interests of its citizens would be damning to its image on the world stage. Unfortunately, money is the dominant motivating factor for any meaningful change—or lack thereof—in the United States. As other nations refuse to trade with, travel to, or otherwise engage with the U.S., the resulting economic strain could incentivize those in power to change course.

Moreover, a petition like this, if granted, could open the floodgates for other such petitions and suits to be filed in other courts—not only against the United States but also against any nation failing to adequately protect its citizens from climate change. The precedent set by this action could engulf the United States in further litigation and international law violations, to the point where doing nothing would destroy whatever credibility it has left on the global stage.

The IACHR has a golden opportunity to further shape the already growing body of global climate litigation by granting this petition. For the sake of the petitioners and humanity as a whole, let us hope that they take it.

This article was written by PECC's Energy and Climate Law Scholar Stephen Badea, a first-year law student at Elisabeth Haub School of Law at Pace University. It was originally published on November 10, 2025, in Volume 1, Issue 2 of the R.E.A.C.T. by PECC Newsletter.

Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, Carington Lowe