Articles by Energy & Climate Law Scholars

This page features original research and articles by PECC Energy and Climate Law Scholars on energy and environmental law topics. The highlighted pieces explore emerging legal issues, policy developments, and innovative solutions, showcasing the capabilities of the next generation of environmental leaders.

Rethinking Battery Energy Storage Systems with an Energy Storage Road Map

By: Tamika Thomas-Murray J.D. '26 | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, and Carington Lowe

Towns, villages, and boroughs across New York State are working to meet the demanding requirements of the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act. This legislation has supported the growth of Battery Storage Programs, evolving from small-scale projects mainly used for home resilience to larger Battery Energy Storage Systems ("BESS") projects designed to support resilient communities with a 5MW output to the grid. BESS are viable energy options that help meet the aggressive mandates and aim to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. However, they have unfortunately faced opposition from communities such as Addisleigh Park in Queens and Mariner’s Harbor on Staten Island.

Although there is strong opposition to BESS, the legal landscape supporting battery energy source systems is strong and advancing in New York. New York defines BESS as one or more devices assembled together that can store energy to supply electrical power later (N.Y.S.A. 2025, A.8141). The state has most recently enacted the Renewable Action through Project Interconnection and Deployment ("RAPID") Act, which expanded New York’s power to expedite major renewable projects, including battery storage facilities of 25 MW or larger, even when communities raise safety concerns. This act confirmed case law, such as Glen Oaks Village Owners Inc. v. City of New York, which states that the State's intent to occupy a field may be expressed or clearly stated in the body of legislation or implied through a policy. Preemption, however, occurs when local laws conflict with or supersede a state law, or when additional restrictions are imposed on a state law. The legal principle of preemption has constrained New York’s legislature from fully empowering local governments to pursue clean energy initiatives, thereby limiting the extent to which communities can shape their own transition to a clean energy future, which may delay New York's clean energy goals.

New York’s BESS systems can operate as both mobile and stationary systems, supporting their versatility and making them easier to deploy across communities in the NYC area. BESS will also play a crucial role in providing reliable and affordable power to New Yorkers while addressing “areas with high energy demand.” Additionally, BESS will support New York’s efforts to meet its greenhouse gas emission reduction goals, improve public health, and mitigate the future impacts of climate change. As BESS are expected to help phase out “peaking” power plants (or “peaker” plants) in the move toward full decarbonization, they will enable communities overburdened by GHG emissions and other harmful chemicals to reduce local air pollution from fossil fuels.

While communities oppose BESS, their placement aims to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. The expansion of BESS in parts of the city is supported by Local Law 97 and the “City of Yes for Carbon Neutrality” zoning regulation. Despite the tension between local opposition and state and city climate goals, the expansion of BESS has begun, driven by the urgent need for sustainable and resilient energy infrastructure. Currently, developers like Ninedot Energy and MicroGrid Networks ("MGN") are community-scale battery storage companies operating in the New York City area.

Opponents of BESS often cite concerns about safety, health, environmental impacts, and limited community benefits, but New York has established strict regulations and FDNY oversight to ensure these systems are properly designed, installed, and maintained. BESS plays a vital role in phasing out fossil fuels, which are linked to asthma, pollution, and climate-driven flooding, while also supporting lower electricity costs and providing opportunities for STEM education, green energy training, and student mentorship. By addressing community concerns and highlighting these benefits, BESS projects can build trust and demonstrate their importance in advancing New York’s clean energy transition, which can also be tracked to create transparency for communities.

Community-Centered Just Transition from Fossil Fuels to Renewable Energy

By: Hannah Frizzell J.D. '27 | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, and Carington Lowe

The global transition from fossil fuels to renewable energy has accelerated significantly in recent years. Although the transition was initially driven by environmental concerns, this shift is now equally motivated by economic incentives. Countries such as China have heavily invested in renewable infrastructure to reduce long-term costs and enhance energy independence. Contrarily, the transition in the United States has been anything but linear. Although the West Coast has rapidly incorporated solar and wind power, the Rust Belt remains tied to the fossil fuel industry.

A “just transition” is the policy framework that supports a shift to a low-carbon, environmentally sustainable economy that is fair and inclusive. This transition in the Rust Belt continues to face multiple challenges—such as shifting federal priorities, politicizes skepticism of renewables, and structural barriers to adoption. Moreover, the fossil fuel industry not only provides employment opportunities to these communities but also funds local infrastructure, educational opportunities, and community life. Overall, this economic and societal dependence on fossil fuels creates unique obstacles for the Rust Belt communities.

For the Rust Belt to justly transition from fossil fuels to renewable energies, the policy framework must prioritize more than institutional and economic stability and must also incorporate community empowerment and place-based assessments. Strong and well-developed institutions play a vital role in establishing and implementing regulatory frameworks for clean energy and environmental policies. Political scientists theorize that successful renewable energy transitions depend not only on environmental and energy policies but on strong and effective institutions. Although economists agree that institutional stability is important to a just transition, they contend that a stable financial sector within the clean energy industry is vital. A stable financial sector permits the comprehensive framework to build its plans on a monetary foundation, allowing investors to confidently invest within the renewable regime.

The Inflation Reduction Act ("IRA") consolidates these policy dynamics into one comprehensive framework aimed at providing place-based incentives for the financial sector to invest in areas historically dependent on fossil fuel industries known as “energy communities.” Central to these incentives were the Investment Tax Credit ("ITC") and Production Tax Credit ("PTC"), through which energy projects would receive a 10% tax credit bonus that would significantly lower project costs and increase their overall value (IRC §§ 45Y and 48E). For the ITC and PTC bonuses to vest in the energy projects, companies must meet the Prevailing Wage and Apprenticeship ("PWA") requirements determined by the Secretary of Labor. The PWA required taxpayers to ensure that laborers and mechanics employed in the construction, alteration, or repair work were not paid less than the prevailing wage rate for work performed with respect to a qualified facility for the particular tax incentives. Once eligible for the base ITC or PTC, projects could also qualify for the Domestic Content Bonus. The Domestic Content Bonus is an additional tax credit that energy projects receive if they purchase American materials, such as steel, iron, solar panels, and wind towers.

Unfortunately, the IRA’s implementation is now limited due to the shift in federal leadership. The One Big, Beautiful Bill Act ("OBBB"), signed into law by President Trump, significantly weakened the IRA’s clean energy incentives. Under the IRA, energy projects commencing as late as 2031-2034 could fully qualify for ITC and PTC bonuses. However, the OBBB now imposes an accelerated phase-out, requiring clean energy projects to commence construction by the end of 2027 to receive the base credits offered by the ITC or PTC. Additionally, the OBBB severely restricts the Domestic Content Bonus. If a project obtains foreign materials from a Prohibited Foreign Entity, such as China, the project loses not only its Domestic Content Bonus but also any ITC or PTC bonuses.

Despite the OBBB’s rollback on clean energy incentives, some Rust Belt regions continue to pursue a just transition framework, placing a greater emphasis on community empowerment and place-based assessment. For example, Southern West Virginia is a region that suffered not only from a dramatic decline in coal production but also from a targeted deployment of opioids that made the region ground zero for the national opioid epidemic. While the passing of the IRA helped catalyze momentum for the clean energy development, it also required the region to expand in partnerships to support sustainable, community-trust growth.

To begin repairing this region that has been vastly affected by socioeconomic disruptions, West Virginia leaders partnered with institutional and industry leaders to transform 21 Southern West Virginia counties into a hub for clean energy jobs. This transformation is documented through the Appalachian Climate Technology (the "ACT Now") portfolio, which recognizes the unique dedication and commitment many West Virginians feel toward their state. Community-based organizations such as Coalfield Development, West Virginia Community, and West Virginia Generation have been the driving forces behind ACT Now, working to address systemic challenges for rural development from local bottom-up directives, rather than through top-down federal mandates.

The community-based organizations expanded their partnerships to private institutions, such as West Virginia University and Marshall University, as well as unions representing carpenters, mine workers, and utility workers. With this strong institutional and financial stability across the coalition, ACT was awarded the federal Build Back Better Regional Challenge ("BBBRC") grant. Key projects ACT is now pursuing include transforming abandoned mines to sustainable lands, rewiring Appalachia to expand solar energy access, and developing a LIFT Center, which is a manufacturing plant being transformed into a multi-purpose center for job training, battery research, and repurposing EV batteries for solar energy storage. ACT Now’s efforts suggest that a just transition succeeds when community empowerment and place-based assessment are central to the framework, supported by institutional and financial stability.

The U.S.-China Divide in Solar Policy & Deployment

By: Kaden Bosquez J.D. '28 | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, and Carington Lowe

The Bureau of Land Management’s ("BLM") recent cancellation of the programmatic environmental review of Esmeralda 7—a project once envisioned to be North America’s largest utility-scale solar development—is a microcosm of a shift in U.S. energy policy. Not only is it a return to fragmented permitting processes that lengthen deployment timelines and raise costs, but it also slows progress toward national renewable-energy goals and toward meeting the country’s compounding energy demands.

Meanwhile, China continues to surge ahead, adding record solar capacity each year under a unified national strategy that integrates manufacturing, deployment, and financing. The contrast is glaring: as China consolidates its dominance over the global solar industry, the U.S. risks entangling its own energy future in regulatory paralysis and policy reversals.

Formally proposed in late 2023, Esmeralda 7 consisted of seven individual solar projects and accompanying battery energy storage systems ("BESS") planned for federal rangeland in Esmeralda County, Nevada. The project’s environmental review area covered roughly 62,000 acres of BLM-administered land and was projected to produce 6.2 gigawatts of solar power—enough to supply nearly two million homes. While BLM’s NEPA register lists the project as “cancelled,” the Department of the Interior ("DOI") characterized it not as a termination but as giving each of the individual developers “the option to submit individual project proposals to the BLM to more effectively analyze potential impacts.” Without a consolidated permitting framework, each developer must now undertake a separate NEPA process with its own scoping, comment period, and potential litigation—effectively resetting the approval timeline and creating uncertainty for the U.S. supply chain.

Programmatic permits have long been recommended to reduce permitting and deployment timelines by addressing environmental, land-use, and compliance questions collectively under the relevant federal statutes and regulatory rules. They also allow the United States to accelerate energy-project deployment while balancing environmental impacts.

The decision to alter the permitting process for Esmeralda 7 is the latest of many decisions that shift U.S. energy focus away from intermittent renewable sources. While DOI announced emergency efforts to streamline permitting to meet surging electricity demand, the initiative excluded solar or wind energy projects, instead prioritizing oil, natural gas, geothermal, nuclear, and hydropower. Moreover, DOI has reversed or re-examined lower-fee rules for solar and wind rights-of-way and paused new leasing rounds for policy review, while the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency has terminated grant programs that expanded solar access in low-income communities.

Most notably, the One Big Beautiful Bill Act ("OBBBA"), passed earlier this year, substantially accelerated the phase-out of and narrowed eligibility for clean-energy tax credits. The bill withdrew predictable tax incentives that underpin project financing, reducing the bankability of new wind and solar projects, increasing the cost of capital, and slowing deployment of renewable generation and grid-scale battery storage.

Predictable permitting policies and procedures help signal to banks that renewable energy projects are worthy lending opportunities and to component producers that there is demand for the critical materials used in solar projects. Today, however, regulatory uncertainty and the loss of key tax credits are shrinking renewable energy investment forecasts in the United States, chilling private sector investment at a time of record-high energy demand.

This policy environment stands in sharp contrast to China’s current renewable energy trajectory. Over the past decade, China has treated solar as both an industrial and energy-security priority. The International Energy Agency ("IEA") reports that China accounts for nearly 95% of global wafer and polysilicon production and roughly 80% of the world’s solar-module manufacturing capacity. In 2024 alone, China added approximately 277 GW of new solar power—over 60% of global solar installations that year.

The U.S. solar-manufacturing base remains limited: domestic module output still trails demand, and many components are imported. On the deployment side, the United States installed roughly 50 GW in 2024—an all-time domestic record but still an order of magnitude lower than China’s annual additions. According to the IEA’s Solar PV Global Supply Chains report, Chinese production costs for solar modules remain 30% and 35% lower than those in the United States and Europe respectively, due to economies of scale, lower capital costs, and consistent policy support.

China’s centralized planning integrates manufacturing, deployment, and transmission expansion under a unified industrial strategy. The United States, by contrast, manages its renewable deployment through a patchwork of federal, state, and local authorities. However, when major projects like Esmeralda 7 are cancelled or programmatic reviews abandoned, the inefficiencies of this decentralized approach are exposed, further reducing investor confidence and destabilizing domestic renewable energy permitting and procurement.

This contradiction is especially striking given that U.S. electricity consumption is expected to rise by 2.5% annually over the next decade, driven largely by electrification and the rapid growth of AI data centers. Meeting that demand with clean energy will require consistent, streamlined project review processes, as well as robust manufacturing and deployment incentives. Solar generation in particular has the shortest average permitting timeline among renewable sources. However, programmatic reviews—such as the one originally planned for Esmeralda 7—remain among the few tools capable of aligning environmental compliance with rapid deployment.

While China continues to consolidate its lead in solar through scale, coordination, and industrial policy consistency, the United States faces a bottleneck of permitting complexity and policy reversals that slow its ability to meet domestic demand and compete in the global clean energy market.

If the United States is to meet the call of today, it will need to align its permitting architecture with its industrial policy ambitions. Otherwise, the world’s largest energy consumer will remain a step behind in building the energy systems that will power its future.

New York State's Energy Blueprint

By: Frank Mattimoe J.D. '28 | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, and Carington Lowe

New York’s Governor Kathy Hochul announced in June 2025 that the New York Power Authority ("NYPA") should begin developing plans to permit and construct an advanced nuclear energy plant in Upstate New York. The planned facility would produce at least one gigawatt ("GW") of energy, adding to the state’s 3.4 GW current nuclear energy generation mix. The new plant announcement brings into motion the second stage of the governor’s New York Nuclear Energy Master Plan, the blueprint announced during her State of the State address in January 2025 (the “Blueprint”). The Master Plan seeks to decarbonize the state’s economy and address rising energy needs from the semiconductor industry, Artificial Intelligence, and the electrification of the state grid. During the State of the State, the governor also announced a ten-state consortium whose work would help standardize reactor designs, drive down costs, and create a pipeline for private sector entities to get involved in advanced plant construction.

The Blueprint refers to an “advanced” reactor as “recently designed” and incorporating versatile safety and operational capabilities. Advanced reactors include both light-water reactors ("LWRs")—the only commercially operated type of reactor in use in the country—and non-LWR facilities, which have been tested in the country, though they have not yet been made commercially viable. New York State currently operates three LWR reactors; its fourth reactor at Indian Point was shuttered in 2022 over concerns that the plant sat on an earthquake-prone fault line, withdrawing massive amounts of water from the Hudson River. Some state Democrats, including Rep. Ritchie Torres, have expressed regret at the plant’s closure, which increased emissions by 22 percent from 2019 to 2022 and cost consumers $300 million more for their energy needs. State Republicans and Democrats alike are now seeking to host the newly announced facility in their districts. Constellation Energy, which runs the state’s three remaining nuclear facilities, has signaled its interest in partnering with NYPA to construct the new plant.

Despite this renewed interest inside Albany in pushing nuclear power, there remain some concerns, particularly surrounding the cost of the new plant. The cost of maintaining the state’s previous four existing plants ran at $500 million annually, an exorbitant amount compared to nonrenewable sources. There are likewise concerns that costs will mount during the construction and permitting phase. The nation’s most recent nuclear reactors, the only ones built in the past 30 years, Vogtle 3 and 4 in Georgia, doubled in cost and in their construction timeline, reaching $36 billion over 15 years after the bankruptcy of their contractor, Westinghouse.

Washington seems to be signaling that it will push for industry-wide deregulation that will prevent these roadblocks from arising in future nuclear plant construction. The Trump administration released four executive orders the week after Governor Hochul’s June announcement, seeking to “usher in a nuclear renaissance” by promoting both the deregulation of plant permitting processes and the bolstering of national energy supply chains. Relevant to New York in these early stages is a directive to “significantly expedite review, approval, and deployment of advanced reactors ... within two years” of approval, and to streamline environmental reviews for advanced reactor proposals. The Executive Orders also seek to “modernize” the Nuclear Regulatory Commission’s regulatory process to include an 18-month deadline to begin construction on new plants. With the Trump administration reducing a major regulatory hurdle that contributed to cost overruns, the new plant may be approved more quickly and avoid some of the initial cost concerns that have made nuclear plants so challenging to build. The governor’s Blueprint cited the steep costs associated with the Vogtle turbines and stated that it would work to develop appropriate supply chains, demonstration facilities, and cooperation with other states—a process that has already begun with the multi-state consortium plan. Even with reductions in the review process, however, the onus of responsibility will be on New York State to ensure that cost-overrun risks are mitigated, allowing the state to enjoy the clean energy promised by Governor Hochul.

Brazil as a Sustainable AI Hub in the Global South: A Comparative International Law Analysis

By: Isabela Vasconcelos Chelou LL.M. | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, Carington Lowe

Brazil is rich not only in culture and population but also in natural resources. It is known for its diverse biomes and is the Latin American country that contains the largest portion of the Amazon rainforest. Brazil has an abundance of powerful rivers and forest reserves that sustain the water cycle, as well as strong winds and high solar incidence across its continental territory. The country’s extensive climate agenda is part of the reason why Brazil will host COP30 this year. The event will take place in the city of Belém do Pará, currently one of the largest cities in the Amazon and commonly referred to as a gateway to the forest.

Precisely because it leverages many advantages in terms of natural resources, Brazil is one of the leading countries in producing clean energy. According to Brazil’s EPE, 88.2% of the country’s electricity in 2024 was renewable, with solar and wind making up almost a quarter of the total. Looking at low-carbon electricity, which includes hydropower, the country’s power grid is one of the world’s most sustainable, with 90% of its 2024 electricity coming from low-carbon sources, including 56% hydropower and 24% wind and solar, according to data released by Ember.

Due to this great potential to generate renewable energy, Brazil has been attracting an increasing number of Big Tech companies, like Amazon and Microsoft, seeking to invest in the construction of large artificial intelligence data centers. Moreover, such interest demonstrated by Big Tech companies aligns closely with Brazil’s goals at both governmental and private levels, particularly because investments from such companies stimulate technological innovation and position Brazil as a pioneer in Green AI in Latin America.

Nonetheless, to become a superpower in sustainable artificial intelligence, Brazil will also have to deal with challenges, including but not limited to the high energy and water consumption required by data centers, a significant risk of “data extractivism”, and unequal access to energy. Big Tech companies may enjoy privileged access to a continuous energy supply, while vulnerable populations face limited access to electricity.

This can be particularly complicated, considering that Brazil does not yet have specific legislation regulating AI data centers. Although the country has strong environmental licensing laws—most notably Law No. 6.938/1981 (National Environmental Policy)—which requires an environmental impact study as part of licensing for major projects, these laws were primarily designed to regulate factories, hydroelectric dams, mines, and large infrastructures, as these typically have significant and visible ecological consequences that trigger the need for an impact study.

However, the environmental damage left behind by digital infrastructures is often less visible. The high water and energy consumption demanded by AI data centers can have long-term negative effects that may not be immediately apparent and thus may not trigger the need for an environmental impact study. This regulatory blind spot can mean that a large data center could pass through with a less rigorous process. Therefore, because the AI data centers are a recent technological development, the existing Brazilian laws have proven incapable of properly targeting digital infrastructures.

This legislative gap has not gone unnoticed by the Brazilian legislature, which is already working on Bill No. 3018/2024 (Projeto de Lei nº 3018/2024) (the “Bill’), filed in August of 2024. Still in the early stages of proceedings in the Federal Senate, the Bill, in its proposed Article 5º, enumerates the measures that AI data centers need to follow to guarantee energy efficiency and environmental sustainability. This list includes the use of renewable energy sources, efficient cooling systems, and optimized hardware. It also requires that energy audits must be conducted periodically and that annual energy reports must be published. Another interesting measure proposed by the Bill is the development of management plans that include greenhouse gas emission reduction targets, as well as the promotion of recycling and proper disposal of electronic equipment.

If enacted into law, the proposed Bill would resemble the model adopted by the European Union, which already has a regulatory directive for AI data centers in effect. This is binding legislation, and Member States are required to transpose it into national law and ensure its enforcement. According to Article 12 of the Energy Efficiency Directive (Directive (EU) 2023/1791), large data centers that operate above 500 kW are required to report annually on their energy performance.

This annual report must fulfill the minimum requirements set out in Annex VII of the Energy Efficiency Directive. Aside from basic identification information regarding ownership, location, installed power, and data traffic, the directive also specifies, in Subsection (c) of Annex VII, that Key Performance Indicators (“KPI”) shall be monitored and published in observance of Article 12. It defines a non-exhaustive list of such indicators, including energy consumption, power utilization, temperature set points, waste heat utilization, water usage, and use of renewable energy. The first evaluation following this directive was published on July 8, 2025, showing that this is innovative legal ground in the European Union, as it is in Brazil.

Finally, Article 12 makes it clear that the reporting obligations are not aimed solely at monitoring data centers. The collected information may result, when appropriate, in proposals for new legislation to further strengthen energy efficiency, with the goal of transitioning toward a net-zero emission data center sector. In other words, the European Union will use the data reported annually as sustainability metrics to examine and study ways to continue improving. This feedback mechanism will, in turn, incentivize policymakers to prioritize clean energy sources and reduce reliance on fossil fuels.

Because it is still in early stages, the Bill has yet to develop its reporting obligations, enforcement authority, and penalties. Additionally, Brazil needs to define its operational threshold and establish which AI data centers will fall under its scope. The European Union could serve as inspiration, and considering that Brazil is hosting COP30, it is the perfect opportunity to learn from other countries’ existing AI regulation models and use their strengths and shortcomings as guides when refining Bill No. 3018/2024—potentially becoming a reference for the next generation of sustainable technology law.

However, the Brazilian legislature is not the only one that should be drawing on outside references; the legislative gap is even deeper in the United States. With no binding federal regulation on energy efficiency standards or reporting obligations for AI data centers, the U.S. mainly relies on a self-regulatory approach. This means that large tech companies establish and enforce their own energy consumption standards, which end up being cost-driven rather than sustainability-focused. The Environmental Protection Agency (“EPA”) launched the ENERGY STAR program—a voluntary certification for U.S. data centers—in an attempt to promote better energy-use practices among Big Tech companies.

Yet companies are not required to participate in this program, despite the EPA’s recognition that “data center energy use was predicted to grow exponentially as digital computing expanded. However, gains in energy efficiency—both at the network hardware and storage level, as well as at the building level—have mostly offset this growth.”

Despite having two proposed bills to address the environmental impacts of AI data centers, notably—the Artificial Intelligence Environmental Impacts Act of 2024 (S.3732/H.R.7197) and the Department of Energy AI Act (S.4664)—the U.S. Congress has not yet introduced any bills mandating energy efficiency standards or reporting and monitoring duties.

This lack of incentive appears to stem from the nation’s continued reliance on fossil fuels. According to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, in 2024, only 26% of the country’s electricity came from renewable sources, while 54% came from fossil fuel sources and 18.6% from nuclear power.

The comparison between Brazil, the EU, and the U.S. highlights the necessity for a more harmonized global approach. Artificial intelligence is transnational, as it is embedded in more areas of society every day. Big Tech’s investments, emissions, and energy use go beyond jurisdictions; therefore, COP30 is an opportunity for recognition that global alignment is essential.

COP30 presents itself as the ideal moment to influence States’ behaviors through the Paris Agreement. Under Articles 6, 9, and 10, the framework could be used to encourage States to adopt incentives such as tax breaks, carbon market benefits, and subsidies to make investment in renewable energy AI data centers more attractive for tech companies.

Linking AI data centers to renewable energy incentives within the financial mechanisms provided by the UNFCCC framework could shape corporate investment decisions, steering Big Tech toward a more sustainable path and discouraging dependence on fossil fuels.

In this context, as COP30 approaches, Brazil should take the lead and establish itself as a trendsetter among the global south, bringing together AI growth and climate responsibility as pillars for an advanced and sustainable future for all, demonstrating how its renewable energy advantage can inspire a new global standard.

The Forgotten Half of Climate Justice: What COP30 Must Remember About the Ocean

By: Ayman Irfan S.J.D. | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, Carington Lowe

COP30 in Belém will undoubtedly spotlight the Amazon, but the true measure of global climate ambition may lie elsewhere—in the ocean. For decades, the ocean has served as the silent stage of climate politics: acknowledged as a “carbon sink,” lamented as a casualty of rising temperatures, and then quietly sidelined when decisions are made. That silence may finally be breaking.

Recent advisory opinions from the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea (“ITLOS”) and the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) have redefined what it means for States to protect the marine environment. For the first time, the world’s highest courts have affirmed that States carry binding obligations—not voluntary pledges—to prevent harm to the ocean caused by climate change.

These rulings go beyond legal interpretation. They expand the boundaries of our moral and political imagination, reminding us that protecting the marine environment is not just about reducing carbon—it is about confronting every way human activity that destabilizes the ocean system. Many of those pressures remain largely ignored.

As the world prepares for COP30, three critical yet overlooked fronts will determine the future of ocean protection and, with it, the integrity of global climate justice.

The Deep Sea, Climate’s Final Frontier

The deep sea covers half the planet yet remains one of the least understood ecosystems on Earth. It is also the new frontier for industrial extraction. A growing number of companies are lobbying to begin deep-sea mining, scraping the ocean floor for minerals needed for renewable technologies.

Scientists warn that disturbing the seabed could release trapped carbon, disrupt nutrient flows, and permanently damage habitats that have evolved over millions of years. Once destroyed, they may never recover.

The advisory opinions from ITLOS and the ICJ make clear that States have a duty of due diligence: they must take all necessary measures to prevent harm to the marine environment. That duty extends beyond national borders and includes activities authorized through international bodies such as the International Seabed Authority.

If that standard is taken seriously, it is difficult to see how deep-sea mining can move forward without violating international law. Yet COP after COP has largely ignored the issue.

Belém should change that. The deep sea is not just a scientific curiosity—it is a massive carbon reservoir and a critical part of Earth’s climate system. Recognizing it within the UNFCCC framework could be a turning point. The advisory opinions give countries the legal basis to demand exactly that.

The Next Biodiversity Battle: Marine Genetic Resources

A second quiet revolution is happening at the microscopic level. Marine genetic resources—the biological material found in deep-sea organisms—are now prized for their potential in medicine, biotechnology, and even carbon capture.

The 2023 Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (“BBNJ”) Agreement, sometimes called the “High Seas Treaty,” was designed to ensure that these resources are used fairly and sustainably. But it is still awaiting full ratification, and climate negotiators have yet to grasp its implications.

The advisory opinions provide clues. Both courts emphasized that equity and intergenerational justice are binding principles under international law. That means States cannot exploit ocean life for commercial gain without considering who benefits and who bears the ecological cost.

At COP30, parties could begin linking marine genetic resources to climate adaptation finance. The ocean’s genetic diversity underpins its resilience, and protecting it is a form of climate adaptation in itself. Ensuring that profits from ocean biotechnology help fund conservation would be a powerful expression of the equity the advisory opinions demand.

Ocean Loss and Damage

When negotiators talk about “loss and damage,” they usually mean flooded homes, failed crops, and climate refugees. Rarely do they mention dying coral reefs, collapsing mangroves, or disappearing fish stocks—losses that devastate coastal and island nations.

The new Loss and Damage Fund established at COP28 was a historic step forward, but so far it remains almost entirely land-focused. There is no mechanism to measure, let alone compensate for, ecological losses in the ocean.

Yet the ICJ’s advisory opinion makes clear that States may be responsible for transboundary environmental harm. That principle could be extended to marine ecosystems. If one country’s emissions destroy coral reefs or fisheries vital to another nation’s survival, the logic of loss and damage should apply.

COP30 could be where this conversation is finally prioritized. An “Ocean Loss and Damage” framework focused on restoration, blue carbon recovery, and ecosystem resilience would bridge the gap between the climate and ocean regimes. It would also honor the courts’ declaration that the duty to protect the marine environment is a global obligation owed to all humankind.

Listening to the Ocean

The common thread across these issues—from deep-sea mining to genetic equity and ocean loss and damage—is that they challenge us to see the ocean not as a passive victim but as a living system with legal rights and global significance.

The advisory opinions have shifted the baseline. Environmental protection is no longer a matter of goodwill or policy preference—it is a legal duty enforceable under international law. That recognition should embolden States, civil society, and regional coalitions to push harder for concrete ocean action at COP30.

The Absence of International Renewable Energy ‘Hard Law’

By: Sophie Bacas J.D. '26 | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, Carington Lowe

In the months preceding COP30, the ICJ delivered its Advisory Opinion affirming that international law requires all States to prevent significant environmental harm, and that the environment must be protected for present and future generations. Law creates and maintains an architecture for realizing common needs and satisfying societal aspirations. International law shoulders the heaviest burdens, as it functions to achieve international solutions for global problems and lays the groundwork to satisfy aspirations for a better world. The solutions provided by international law are imposed on sovereign nation-states who provide their consent—for example, by agreeing to the terms of a treaty or recognizing a principle of international law. In doing so, States limit their sovereignty but open themselves to collaboration and development. Such progress is only heralded by “hard” international law and merely encouraged by “soft” international law.

While treaties and customary international law are hard law, yielding legally enforceable obligations and imposing sanctions for noncompliance, soft law—such as agreements and declarations—dominates the international stage, as it provides guidance and influence without authority. Soft international law has therefore become the predominant mechanism for discourse regarding global climate change redress, including matters concerning renewable energy. As the world barrels toward a warming limit of 2°C above pre-industrial levels, alternative energy sources are increasingly necessary in lieu of energy produced by the combustion of finite fossil fuels. Despite this reality, hard law solutions on renewable energy are notably lacking on the international stage; however, alternative agreements and pledges may pave the way for binding solutions soon. These binding agreements could arise from the mandates set forth by the ICJ, which clarified that States’ obligations under international law not only encompass those set forth in climate treaties but also extends to customary international law duties to prevent significant harm to the environment.

In December 2023, 118 States pledged to increase the global renewable energy capacity and increase the annual rate of energy efficiency improvements by 2030. The Global Renewables and Energy Efficiency Pledge (“COP 28 Pledge”) marked an important step in accomplishing the objective of the 2015 Paris Agreement, which aimed to limit global warming below 1.5°C. Specifically, the COP28 Pledge sought to triple the world’s renewable energy capacity to 11 TW by 2030 and double the average annual rate of energy efficiency improvements every year until 2030. While the COP28 Pledge was a groundbreaking achievement in collectively acknowledging that increased renewable energy use and production are necessary in a warming world, these goals are not grounded in legal authority. Sanctions and consequences are absent from the COP28 Pledge’s language, providing no provisions for holding signatory States accountable if they fail to meet their goals. Additionally, for the stated goals of the COP28 Pledge to yield tangible results, national policies are required for implementation. To date, national policy implementation for renewable energy transitions would only be achieved through the voluntary action of signatory States, with no recourse for failure. Time will tell how the ICJ Advisory Opinion will impact that potential recourse.

The singularity of the COP28 Pledge and its lack of legal consequence highlight a greater absence in the field of international environmental law. Following the 1972 United Nations Conference on the Human Environment in Stockholm—the first world conference on the environment— landmark conferences on global sustainable development have produced binding treaties and customary international law compelling States and international actors to reduce air and water pollution, preserve wildlife and biodiversity, protect oceans, manage hazardous waste safely and effectively, and limit ozone depletion, among other goals. However, a mandatory transition away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy—for the purposes of limiting air pollution, providing safe and effective energy to States, and mitigating global climate change—is lacking from this list, despite offering a tangible solution for a shared problem. Many States, such as Sweden, Costa Rica, and the United Kingdom, have already transformed their energy systems to rely on renewables; however, international law mandating renewable energy transitions has failed to materialize.

While the doctrine of stare decisis does not apply to international law, previous covenants have emphasized the necessity of renewable energy development and installation. For example, the 1992 United Nations Conference on Environment and Development and the subsequent adoption of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (“UNFCCC”) highlighted the importance of renewable energy adoption in combating climate change. Similar major agreements include the Kyoto Protocol, advocating for increased renewable energy use in Article 2; the Paris Agreement, encouraging sustainable development and greenhouse gas reduction; and the formation of the International Renewable Energy Agency ("IRENA"), supporting the transition to a sustainable future by promoting the adoption of new forms of renewable energy. However, current hard law does not establish an international renewable energy agreement. Energy is a crucial staple of modern life and technology—necessary for everything from transportation to education to health and innovation—yet cleaner and more sustainable pathways for its production have not been codified within binding international law. This absence must be addressed, and it is for this reason that a binding international agreement calling for increased capacity, development, and installation of renewable energy is urgently needed.

The Future of Cap-and-Trade Markets Following the ICJ Advisory Opinion on Climate Obligations

By: John (Jack) W. Finn J.D. '26 | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, Carington Lowe

In July 2025, the International Court of Justice (“ICJ”) delivered a landmark advisory opinion on the Obligations of States in respect to Climate Change. The Court affirmed that States have obligations under international law to protect the climate system from anthropogenic greenhouse-gas (“GHG”) emissions, to regulate activities under their jurisdiction—including those of private actors—and that a breach may constitute an internationally wrongful act, with possible reparations.

For practitioners of climate policy, particularly those focused on emissions-trading systems (“ETS”) or cap-and-trade mechanisms, this ruling carries profound implications. It repositions market-based mechanisms like cap-and-trade from options among many tools that must align with—and help fulfill—States’ newly clarified obligations.

Overview of Cap-and-Trade Systems

Cap-and-trade (or emissions-trading) systems function by having the government establishing a “cap” on total emissions from covered sources, allocating or auctioning allowances consistent with that cap, and allowing entities to trade those allowances. Entities whose emissions are lower may sell excess allowances, while those whose emissions are higher may buy them, creating a market-based price signal for carbon.

Key design features include: the level and rate of decline of the cap over time; allocation method (free vs. auction); monitoring, reporting, and verification (“MRV”) of emissions; allowance banking or borrowing; and complementary policies. Several jurisdictions have long experience with these systems, including the EU Emissions Trading System (“EU ETS”) and the California Cap-and-Trade Program (U.S.). These models offer practical data and key lessons to learn from.

Cap-and-Trade has been heralded for combining economy-wide emission limits with cost-effectiveness and flexibility. However, the legal framing of such systems has traditionally regarded them as domestic policy choices rather than instruments tied to international obligations.

Linking Cap-and-Trade to the ICJ Opinion

The ICJ Opinion firmly established that States’ obligations are not merely aspirational. These obligations derive from (a) treaty law (such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) and the Paris Agreement), (b) other branches of international law (international human rights law, the law of the sea, and customary international law), and (c) due diligence obligations to regulate private actors under their jurisdiction.

Among the key clarifications:

- Even if States are not a party to specific climate treaties, they remain bound via customary international law to protect the climate system. States must cooperate to reach concreate emission-reduction targets and take measures consistent with the scientific consensus (e.g., limiting warming to 1.5 °C).

- A failure to take appropriate regulatory or legislative measures—including those related to production, consumption, and subsidies of fossil fuels—may amount to a wrongful act attributable to the State.

- The obligations extend to regulating private-sector entities under a State’s jurisdiction.

What this means for cap-and-trade is that market-based mechanisms must be designed and operated in a way that demonstrably contributes to the fulfillment of these obligations. If a State relies on a cap-and-trade system, that system must be configured so that the cap aligns with the State’s overall obligation, the trading regime does not undermine achievement of the objective, and the regulatory oversight ensures that private actors’ emissions are adequately controlled.

Design Implications

- Ambition of the Cap

Considering the ICJ advisory opinion, the cap cannot be arbitrary or loosely tied to business as usual. It must be compatible with limiting warming to 1.5 °C and consistent with the State’s national circumstances and contribution to cumulative emissions. Therefore, when designing a cap-and-trade system, setting the cap becomes an exercise in fulfilling an international legal duty, not simply a policy objective.

- Regulation of Private Actors

One of the Court’s novel points is the obligation of States to regulate private-sector behavior under their jurisdiction. In a cap-and-trade system, this suggests that the allowance market must be accompanied by robust MRV frameworks, compliance enforcement, and accurate accounting of offsets and banking. If private actors evade obligations such that the aggregate cap target is undercut, the State risks failure of its due-diligence obligations.

- Complementarity and Integrity

Cap-and-trade cannot exist in isolation from other policies. The ICJ emphasized that emission-reduction obligations derive from a spectrum of legal sources, including human-rights and environmental treaties; thus, a cap-and-trade system must maintain environmental integrity (e.g., avoiding vagueness, double-counting, or loopholes). For example, linking with other markets should occur only when those systems have compatible standards of integrity.

- Transparency, Accountability, and Legal Consequences

Given that the ICJ advisory opinion links failure to act with wrongful acts, States now face heightened legal risk if their systems are weak, misdesigned, or fail to deliver. Reparation, non-repetition, and restitution are legal consequences. Thus, designers of cap-and-trade systems must build institutional frameworks that can demonstrate compliance, including periodic shrinkage of the cap, public disclosure of performance, and mechanisms to correct underperformance.

- Equity and Historical Responsibility

The Court noted the relevance of States’ contributions to cumulative emissions and the needs of vulnerable developing countries. While cap-and-trade tends to emphasize cost efficiency, the legal context now adds an equity dimension: how free allocations are handled, how auction revenues are spent (e.g., facilitating adaptation, loss and damage), and how burdens are shared. Although economic design is essential, legal fairness must also be built in.

Why Cap-and-Trade is a Strategic Tool for Fulfilling Legal Obligations

While the legal framing raises the bar for design and implementation, cap-and-trade retains considerable value:

- It sets a firm emissions limit consistent with legal obligations, rather than relying purely on voluntary or national-pledge targets.

- It provides flexibility and cost-effectiveness for emitters, encouraging innovation and lower-cost abatement, thus helping to meet obligations efficiently.

- It creates a transparent price signal, enabling governments to align policy, investments, and regulatory oversight with legal standards.

- When well-designed, it can generate revenue through auctions that States can use to support adaptation, low-carbon transitions, and vulnerable populations—aligning with the broader obligations under international law.

Challenges and Risks

Despite its potential, a cap-and-trade system must be carefully managed to avoid shortcomings that could compromise a State’s legal obligations:

- If the cap is too weak, emissions may remain too high, undermining the obligation to protect the climate system.

- Loopholes (e.g., excessive free allocations, weak offset rules, or banking that delays real reductions) risk eroding environmental integrity.

- If monitoring and enforcement are weak, private actors may evade obligations, and the system may fail to deliver, raising risks under the ICJ framework.

- If the system ignores issues of fairness, burden-sharing, or historical responsibility, it may fall short of the duty to cooperate and act with due diligence, as emphasized by the Court.

- Linking with other systems without equivalent safeguards may import weaknesses and undermine a State’s legal position.

Moving Forward

To operationalize the ICJ ruling via cap-and-trade, States should consider the following action points:

- Align the cap trajectory with scientifically based pathways and ensure periodic review and increasing ambition.

- Ensure robustness of MRV and compliance regimes: regular independent audits, public reporting, credible enforcement penalties, and avoidance of creative accounting.

- Embed equity in design: allocate auction revenues or allowances to support vulnerable communities, adaptation, loss and damage, and capacity building.

- Integrate and cross-check with legal obligations: ensure market design is coherent with treaty-based, human-rights, and customary obligations, and periodically evaluate legal risks.

- Design a phase-out of fossil fuel subsidies and other support for high-emitting activities, aligning with the Court’s emphasis on States’ duty to regulate fossil fuel consumption and production.

- Demonstrate transparency and accountability, ensuring that the system helps a State show it is upholding its international obligations and potentially reducing future litigation risk.

Conclusion

The ICJ’s advisory opinion on the obligations of States in respect to climate change marks a turning point: climate-change mitigation is no longer solely a matter of policy choice but squarely a matter of legal obligation. For cap-and-trade systems, this means the stakes are higher: markets must deliver real-world reductions, be legally defensible, and serve both market efficiency and equity. Well-designed cap-and-trade systems offer one of the most powerful tools for States to meet their international responsibilities, but poorly designed markets may expose States to legal risk and undermine the obligation to protect present and future generations.

As the world prepares for COP30 and international forums increasingly call for accountability, the connection between market mechanisms and international law will only deepen. Policymakers, regulators, and markets must now work together under this new legal paradigm to ensure that cap-and-trade systems make not only economic sense, but also legal and moral sense.

From the Courts to the Commission: How U.S. Youth are Globalizing the Fight for Climate Justice

By: Stephen Badea J.D. '28 | Editors: Mercè Martí I Exposito, Frances Gothard, Carington Lowe

In August of 2015, 21 plaintiffs from all over the United States, all under the age of 18, sued the United States in Oregon federal court. Juliana v. United States alleged that the plaintiffs' constitutional rights to life, liberty, dignity, personal security, and more were being jeopardized by the U.S. government due to its omission to do anything regarding climate change despite full knowledge of its detrimental effects.

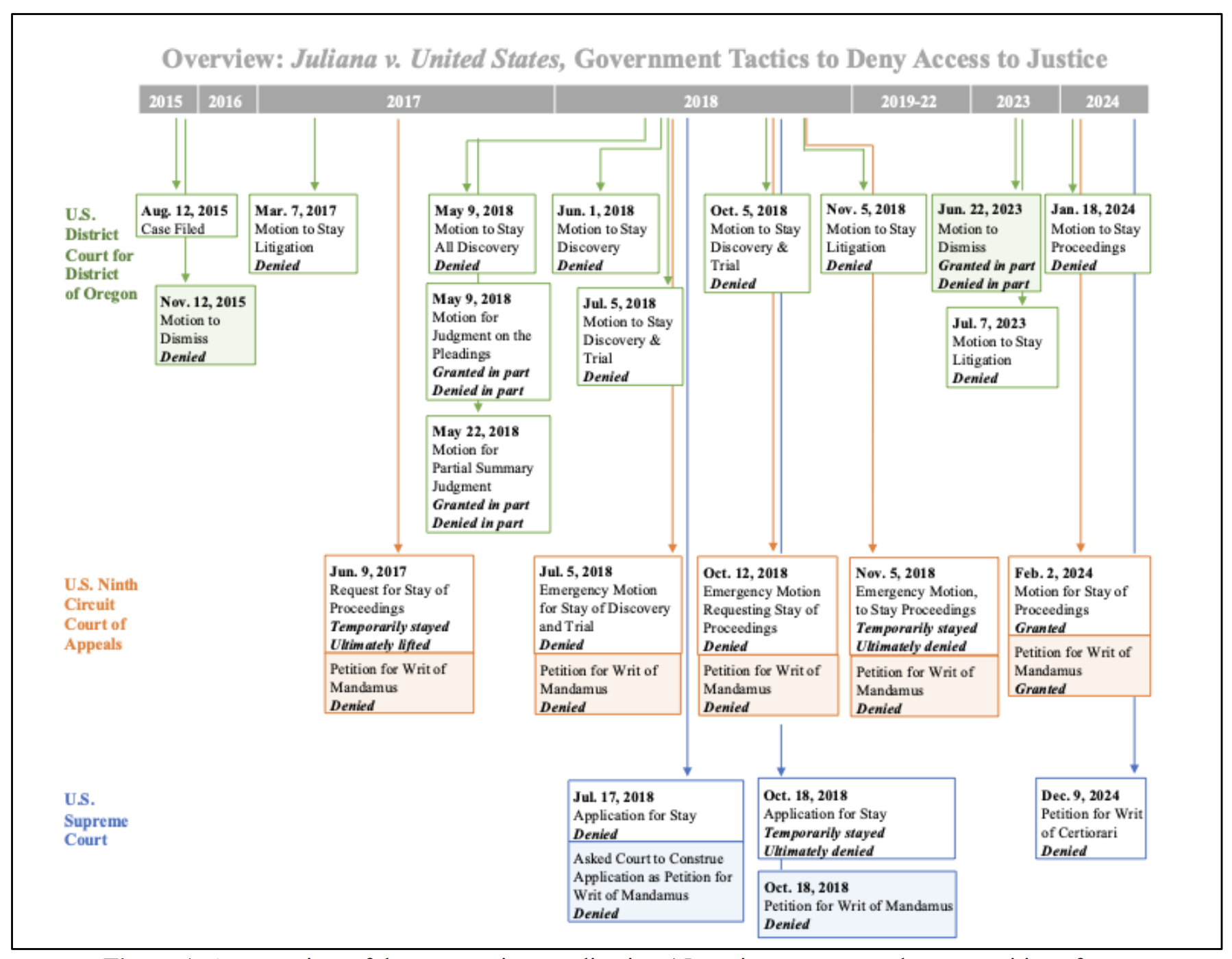

The 21 youths in Juliana litigated tirelessly through all levels of the federal court system for ten years, to no avail. Over that period, they faced relentless opposition and procedural obstruction from the government. The U.S. Department of Justice filed two motions to dismiss, fifteen motions to stay the proceedings, and seven petitions for a writ of mandamus before the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit and the U.S. Supreme Court.

While the Ninth Circuit found that the plaintiffs had proven damages and that those damages correlated with the actions of the U.S. government, the court ultimately decided to remand the case to the District Court on redressability grounds, with instructions to dismiss. In essence, the court stated that the relief the plaintiffs sought was beyond the court’s power, contrary to the opinions of numerous courts worldwide, as well as to several recent influential advisory opinions. Unfortunately, the journey of Juliana through the federal courts ended on March 24, 2025, when the U.S. Supreme Court denied the plaintiffs’ petition for writ of certiorari.

But did the Juliana plaintiffs stop there? Absolutely not.

On September 23, 2025, 15 of the original 21 plaintiffs, represented by Our Children’s Trust, filed a petition to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (“IACHR”), Organization of American States (“OAS”), alleging that the U.S. government’s actions not only threatened their lives but also constituted violations of the American Declaration of the Rights and Duties of Man.

Specifically, the petitioners ask the IACHR to find the United States in violation of Articles I (life), II (equality), V (private and family life), VI (family), VII (special protections for children), IX (inviolability of the home), XI (health), XIII (cultural life), XVIII (access to justice and effective remedies), XXIII (property), and XXIV (prompt and effective remedy) of the American Declaration, and the rights to dignity (Preamble).

While the petition is yet to be decided by the IACHR, it represents a powerful step in the right direction toward ultimately obtaining relief for the Juliana petitioners. By petitioning the IACHR, they are opening the door for international representatives to potentially conduct an on-site visit to the United States and meet with the petitioners themselves to get a firsthand understanding of how United States’ policies not only harm citizens but also undermine human rights as a whole.

Additionally, should the petition be granted, this move by the petitioners would allow the IACHR to conduct hearings as necessary to facilitate further fact-finding. All of this would advance the goal that the Juliana plaintiffs could not achieve in federal court: having a tribunal use its power of judicial review to hold the other branches and agencies of the U.S. government accountable for their willful neglect in addressing the climate crisis.

Even if this were to happen, how would the United States comply?

The IACHR’s recommendations cannot, by themselves, compel the U.S. to act. Despite being a member of the OAS, the U.S. has neither ratified the American Convention on Human Rights nor accepted the Inter-American Court of Human Rights’ (IACtHR) contentious jurisdiction, preventing cases from being brought to or against the U.S. before the IACtHR. Therefore, referral of a petition to the IACtHR would not result in a binding decision against the U.S. Nevertheless, such recommendations could still prompt change through other means. A report from the IACHR explicitly outlining the United States’ human rights violations and repeated failures to act in the best interests of its citizens would be damning to its image on the world stage. Unfortunately, money is the dominant motivating factor for any meaningful change—or lack thereof—in the United States. As other nations refuse to trade with, travel to, or otherwise engage with the U.S., the resulting economic strain could incentivize those in power to change course.

Moreover, a petition like this, if granted, could open the floodgates for other such petitions and suits to be filed in other courts—not only against the United States but also against any nation failing to adequately protect its citizens from climate change. The precedent set by this action could engulf the United States in further litigation and international law violations, to the point where doing nothing would destroy whatever credibility it has left on the global stage.

The IACHR has a golden opportunity to further shape the already growing body of global climate litigation by granting this petition. For the sake of the petitioners and humanity as a whole, let us hope that they take it.

New York Renewable Energy Storage: Futuristic Success or Ongoing Injustice?

By: Samirah Aziz J.D. '26 | Editor: Mercè Martí I Exposito

In early 2025, a massive fire burned for days at a California battery energy storage facility. The disaster forced hundreds of evacuations, raised health concerns, and sparked public backlash. This backlash came not only from Californians directly impacted by the blaze but also from New Yorkers living in municipalities with battery energy storage system (“BESS”) proposals. Although BESS proponents describe BESSs as passive facilities to store unused renewable energy for future use, protesting New Yorkers feared that if BESSs were built near their communities, they could also be in danger.

BESS construction has been increasing in New York given the state’s energy goals in response to the climate crisis. Since 2019, New York has significantly increased its renewable energy use following the passage of the Climate Act, which mandates a 40% reduction in greenhouse gas emissions by 2030. Accordingly, Governor Hochul has encouraged BESS construction as instrumental to reaching the Act’s goals. However, BESSs are relatively recent: the first publicly owned, utility-scale BESS in New York only became operational in 2023.

Additionally, other state laws are implicated within the BESS siting context. In particular, the State Environmental Quality Review Act (“SEQRA”) and the Cumulative Impacts Law (“CIL”) may apply to BESS applicants. In response to Environmental Justice (“EJ”) concerns – including those about municipalities disproportionately siting undesirable land uses near disadvantaged communities – the CIL amended SEQRA to further address equitable siting of environmental projects such as BESSs. Specifically, the CIL provides that BESS applicants may need to include existing burden reports with their applications if the projects have over a "de minimis amount of pollution to any disproportionate pollution burden on a disadvantaged community.” However, this law is limited because it does not require a burden report for applicants seeking BESS modification or renewal, including those who have completed such reports for their BESSs within the past decade. Therefore, the CIL should be amended to require or incentivize existing burden reports for BESS renewal or modification applicants. Such measures would better protect disadvantaged communities from disproportionately bearing the risks associated with BESSs.

BESSs’ Connections to Disadvantaged Communities

Disadvantaged communities’ potential disproportionate impacts from BESS siting stem from Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co. In that landmark case, a village passed zoning ordinances dividing it into distinct use districts. The petitioner challenged the constitutionality of the ordinances since they prevented him from using his property in one district for purposes beyond those permitted within it. The U.S. Supreme Court held that the ordinances were constitutional because municipalities possess flexible police power, granting them discretion over zoning laws as long as the laws are reasonable and enacted “for the public welfare.” However, the Court did not elaborate on the meaning of that phrase, leaving it open to municipal interpretation. For example, municipal zoning regulations often raise residential property values “for the public welfare” in areas located farther from locally undesirable land uses (“LULUs”) while reducing residential property values near LULUs. As a result, disadvantaged communities tend to live in zoning districts near LULUs due to the lack of affordable alternatives.

Although LULUs have traditionally included factories and landfills, BESSs arguably constitute a new form of LULUs. A 2024 American Planning Association report indicates a lack of nationally uniform land use standards for BESSs. This suggests that there is little to no accountability preventing municipalities from siting BESSs in disadvantaged communities, especially given the Euclid precedent. Additionally, the National Fire Protection Association Standard (“NFPA”) 855 requirements for applicants’ approach to BESS hazards fails to provide a “full spectrum of [safety] requirements.” As a result, there is ample grey area that allows municipalities to continue implementing discriminatory zoning ordinances through BESS siting.

Potential Solutions

Based on the overall lack of statewide BESS resources, there is a gap in legislative knowledge on BESSs that should be amended. One potential solution is for municipalities or the state of New York to incentivize BESS renewal or modification applicants to complete existing burden reports. One potential incentive could be a statewide tax benefit for applicants. For example, the Empire State Development agency (“ESD”) has worked with the state to financially incentivize businesses to improve their facilities, among other incentives. New York policy makers, ESD, and other stakeholders should hold ongoing events centered on the potential for similar tax incentives for BESS applicants voluntarily completing existing burden reports. Such events may spur broader discussions about EJ concerns in the BESS and zoning contexts.

Another potential measure would be amending the CIL to require existing burden reports for all BESS applicants. Given the CIL’s voluntary approach to existing burden reports for BESS renewal or modification applications near disadvantaged communities, such an amendment would be ideal for expanding the reach of existing burden reports to all BESS projects shown to have more than a de minimis pollution impact on disadvantaged communities.

Additionally, other potential CIL amendments may supplement the existing burden report requirement to better address EJ concerns. One such amendment could establish a thorough, scientifically and historically informed definition of “disproportionate pollution burden,” which would help SEQRA review agencies make more informed decisions on BESS siting. The CIL could also be amended to include an EJ Working Group, similar to the Climate Justice Working Group that advises the Climate Action Council on the needs of disadvantaged communities. The proposed working group could work closely with the leading agencies on SEQRA approval requirements, scrutinizing each BESS application’s potential EJ impacts and discussing those impacts with the agencies prior to their final decisions. This group could include members from disadvantaged communities located near BESSs. By taking such measures, New York may move closer to a future that works synergistically with disadvantaged communities and renewable energy.

A Bright Future and a Dark Legacy: The Future of Nuclear Energy and Waste Disposal in New York

By: Thomas Glawson J.D. '27 | Editor: Mercè Martí I Exposito

On June 23, 2025, New York Governor Kathy Hochul issued a directive to the New York Power Authority (“NYPA”) to develop and construct a zero-emission advanced nuclear power plant in Upstate New York. This directive comes as New York electrifies its economy, phases out fossil fuel power generation, and continues to attract large manufacturers that demand significant and reliable electricity. Governor Hochul emphasizes an “energy policy of abundance” that centers on ensuring New York controls its energy future, highlighting the "radical increase” in electric supply that will be necessary over the next fifteen years to prevent “rolling blackouts.” This directive is designed to complement existing renewable energy deployment by “adding zero-emission baseload power, providing reliable and affordable clean energy to advance the State’s goal to achieve a clean energy economy” and to meet surging demand from industrial development, building electrification, and electric vehicles.

The NYPA, in coordination with the Department of Public Service (“DPS”), will seek to develop at least one new nuclear energy facility with a combined capacity of no less than one gigawatt of electricity – capable of powering approximately one million homes – either alone or in partnership with private entities, to support the state’s electric grid as well as the people and businesses that rely on it. The NYPA immediately began work on this directive, including site and technology feasibility assessments as well as financing options, in coordination with forthcoming studies included in the master plan for Responsible Advanced Nuclear Development in New York, led by the New York State Energy Research and Development Authority (“NYSERDA”) and DPS. Additionally, this initiative plans to build on existing state financial support for Constellation Energy to pursue early site permitting for a new project at its Nine Mile Point Clean Energy Center, fostering future collaboration with other states and Ontario to strengthen nuclear supply chains.

The plan has received widespread support. Labor unions have praised the initiative for its potential to create thousands of family-sustaining union careers that “pump economic stimulus” into local communities. Business leaders and economic development councils have likewise expressed enthusiasm, emphasizing the need for affordable, reliable, and clean electricity to support fast-growing industries such as semiconductors and artificial intelligence. Environmental groups and experts have also backed the plan, stating that nuclear energy is an “essential strategic asset” for decarbonization and grid reliability.

Despite the initiative’s praise, concerns over nuclear waste remain a key point of opposition. State Senator Liz Krueger stated in a press release: “Can the radioactive material be disposed of in a satisfactory way, or will New Yorkers be stuck dealing with more long-term storage sites like West Valley?” Likewise, Executive Director Stephan Edel of NY Renews, a progressive pro-renewables group, came out against the expansion or further investment in nuclear energy production, expressing concerns over the handling of radioactive materials throughout their lifecycle.

The West Valley Demonstration Project (“WVDP”) is frequently invoked by critics, as its dark legacy looms over New York: “While other countries such as France and Russia recycle nuclear waste, the United States abandoned commercial recycling in the 1970s”. The WVDP was once home to the only commercial spent nuclear fuel recycling center in the U.S., operating from 1966 until 1972, when it shut down due to new regulatory requirements and assessments concluding the site was no longer economically viable, leaving behind 600,000 gallons of liquid high-level waste. It continued as a low-grade nuclear waste storage facility for an additional three years until it was discovered that water infiltration was “caus[ing] contaminated water to overflow from the trenches.”

Congress passed the West Valley Demonstration Project Act in 1980, directing the Department of Energy to solidify and remove the waste from the site, decontaminate and decommission the facility and surrounding property, and – through an agreement with NYSERDA – determine an operational framework for cleanup activities at the site. More than four decades later, West Valley still contains contaminated soil, over fifty casks of high-level radioactive waste with no permanent disposal solution, and remaining cleanup work that could potentially cost billions of dollars. West Valley’s “legacy of toxic pollution” underscores the severe consequences of historical spent fuel processing and magnifies public and legislative anxiety over new long-term storage sites and disposal in New York.

New York statutes strictly govern nuclear waste disposal. For high-level waste, such as spent fuel, permanent terminal storage requires concurrence by statute from the Governor and legislature, requiring NYSERDA to conduct extensive safety reviews and public hearings. For low-level radioactive waste, generators must pay fees to fully recover all state management costs, and title to the waste remains with the generator. Temporary repositories require a certificate from the state board overseeing temporary nuclear waste repository siting, and other state and municipal agents are generally barred from requiring additional approvals.

To overcome this hurdle, New York is seeking innovative solutions for nuclear byproducts. The state’s $300 million venture fund is actively pursuing technologies to recycle nuclear waste into new fuel. Carl Perez, the chief executive of the nuclear services company Exodys Energy, described New Yorkers as “visionaries” for exploring this path. This approach aims to utilize spent nuclear fuel more efficiently; many nuclear power advocates use the term “renewable” to describe the potential of running reactors on recycled waste rather than newly mined uranium.

If successful, Governor Hochul’s nuclear initiative will deliver critical, affordable, and clean energy to New York for generations to come, while creating thousands of jobs and attracting critical business investments. Overcoming the toxic legacy of West Valley and resolving the state’s nuclear waste challenges remains a monumental task that, if achieved, could position New York as a national leader in zero-emission energy and at the forefront of the fight against climate change.

When Washington Stalls, States Power Forward

By: Ashely Hipnar J.D. '28 | Editor: Mercè Martí I Exposito

Federal energy and climate law swings like a pendulum, as Obama’s Clean Power Plan gave way to Trump’s lenient Affordable Clean Energy Rule, followed by Biden’s ambitious Inflation Reduction Act (2022). The result? A federal system that feels unreliable and unstable under the constantly shifting political winds. Meanwhile, states are taking the lead, experimenting with renewable energy mandates, emissions caps, and environmental justice programs. These efforts are not just patchwork fixes, they are real laboratories of “climate federalism” that could outlast the ups and downs of Washington politics.

Federal Volatility

Federal climate and energy policy remains volatile by design. Executive orders are routinely used to reverse prior administrations’ directives: President Biden signed twenty-four reversals in his first hundred days, while Trump rescinded eighty on the first day of his second term. These rapid shifts often stretch statutory authority, bypassing Congress to pursue partisan goals. Meanwhile, legislative gridlock has stalled meaningful bipartisan progress since the 1990s. The recent “megabill”, passed in July 2025, marked a significant rollback of climate initiatives. Judicially, decisions such as West Virginia v. EPA (2022) and the overturning of Chevron in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo (2024) have further constrained federal regulatory power, deepening the instability of long-term energy and climate governance.

State Leadership

While Washington stalls, states have become the backbone of U.S. climate action, advancing durable policies that outlast election cycles. California’s Zero-Emission Vehicle (“ZEV”) mandate, first adopted in 1990 and strengthened fourteen times since, now requires all new passenger cars, trucks, and SUVs to be zero-emission by 2035. This is especially significant as the EPA’s authority to regulate greenhouse gases faces threats from efforts to repeal the Endangerment Finding.

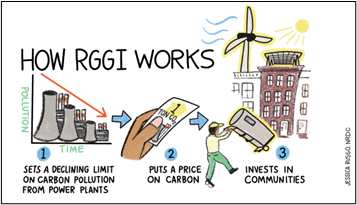

Meanwhile, eleven northeastern states joined forces through the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative (“RGGI”), the “first mandatory cap-and-trade program in the United States to limit carbon dioxide from the power sector.” These eleven states set a regional cap on carbon dioxide emissions from regulated power plants, reducing the allotted emissions over time. Since 2005, RGGI has cut power-sector emissions by 50%, nearly twice the national speed, while generating $8.6 billion for community investment.

New York launched its own initiative in 2019 with the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (“CLCPA”), setting legally binding targets of “100% zero-emission electricity” by 2040 and at least an 85% emissions reduction from 1990 levels by 2050. The Act not only aims to create a healthier New York but also works to increase access to affordable energy through clean solutions, while empowering disadvantaged communities with quality-paying jobs and diversifying opportunities.

Minnesota has a similar plan. In 2023, the state passed a law requiring 100% carbon-free electricity by 2040, with interim steps of 80% carbon-free by 2030 and a requirement that utility retail electric sales increase renewable energy to 55% by 2035. While electrical utilities in Minnesota have decreased carbon emissions from 54% from 2005 to 2020, this law locks in that progress while giving them room to finish the job effectively.

Constitutionality

Environmental protection and public health have never been recognized as enumerated rights under the Constitution, and federal agencies are steadily losing authority in the environmental sphere. This makes federalism central to advancing clean energy standards and climate momentum. Under the Tenth Amendment, powers not delegated to the federal government are reserved to the states, giving them a vital role in regulating energy and protecting natural resources. As Justice Louis Brandeis famously observed, states act as “laboratories” of democracy, testing innovative solutions to pressing social and economic challenges (New State Ice Co. v. Liebmann, 285 U.S. 262, 311 (1932)).

States have broad authority to enact environmental protections but face recurring challenges from federal preemption. In 2024, the Trump Administration issued Protecting American Energy from State Overreach, an executive order aimed at curbing state and local climate policies. Such attempts raise serious constitutional questions, especially given that cornerstone environmental statutes–such as the Clean Air Act–explicitly preserve the ability of states to adopt more stringent standards than federal law.

These tensions are now playing out in court, as fossil fuel companies once eager to remove climate suits to federal forums, are increasingly being forced to defend themselves in state courts after repeated preemption arguments have failed. Right now, the real fight for clean energy is happening in the states, and that is where the momentum lies.